Julius Evola from the perspective of a Catholic Traditionalist (Translation)

Francisco Elías de Tejada, trans. Haniel

Elias de Tejada (1929-1994) was a Spanish professor, philosopher, and jurist aligned with Carlist principles.

Julius Evola (1898-1974) was an Italian philosopher, writer, and political thinker known for his works on traditionalism, mysticism, and esoteric philosophy.

This article originally appeared in the Evolian journal Arthos under the title “Julius Evola alla luce del Tradizionalismo Ispánico” (1974) by Francisco Elías de Tejada. Tailored for an Italian audience, it offers an expository dive into the clash between Hispanic-rooted Catholic Traditionalism (Carlism) and Evolian paganism.

0. Translator's Note

It is not my intention to prolong the discussion within an already extensive article, but it is essential to clarify certain points for those unfamiliar with Catholic traditionalism in general, and Carlism in particular.

Firstly, I have deliberately changed the original syntagma of “Hispanic Traditionalism” (Tradizionalismo Ispánico) to “Catholic traditionalist.” This decision stems from my firm conviction that, unlike other European Catholic movements, Spain uniquely preserved the essence of the pre-revolutionary societas civilis, both spiritually and legally, in a purer form.

Consequently, the political theory of Hispanic traditionalism (of which Carlism is the sole authentic expression) remained doctrinally uncompromised by the political adaptations that later European conservatism undertook in response to the Revolution, whether in the form of absolutism or dictatorship.

This steadfastness can be attributed to the enduring presence of the fuero as the foundational principle of traditional Iberian society, representing local freedoms that were both customary and legally bound to the protection of the monarch. Thus, Carlism consistently resisted the expansion and consolidation of state power in Spain.

In contrast, France, despite the Catholic movement's occasional defense of a federative principle (as seen in Maurras), was deeply entrenched in political and ideological absolutism. Similarly, modern nationalism in other Iberian (Portugal et al) countries posed a doctrinal barrier to the radically anti-modern and anti-bourgeois stance of Carlism.

It is sufficient to state, in defense of Carlism's doctrinal integrity and its prescient understanding of political developments, that both absolutism and commissarial dictatorships inevitably succumbed to bourgeoisification, a process driven by the concessions the nobility and monarchy made to the bourgeoisie throughout the nineteenth century.

Therefore, Carlism, ideologically, aligns more closely with Karl Ludwig von Haller's views than with those of Bossuet or De Maistre. The latter were staunch defenders of monarchical absolutism, a system that inadvertently paved the way for Jacobinism, despite their advocacy for societas civilis and of theological-political principles.

This also clarifies Tejada's disdain for Donoso Cortés, which might seem perplexing to foreign readers (typically ignorant of the Hispanic context and of political traditionalism in general) who, influenced by Schmitt, regard Donoso Cortés as the singular intellectual authority in discussions of political Catholicism in Spain.

This myopia has been notably propagated in the extra-Hispanic academic world (though I will refrain from naming names, I refer to the so-called “Catholic integralism”). The fact is, Donoso was never, strictu sensu, a reactionary. Instead, he defended dictatorship as a modern instrument to both halt the advance of liberalism (especially socialism) and to restore the pre-revolutionary societas civilis. Schmitt, in his misguided interpretation of Donoso, focuses solely on the commissarial aspect of dictatorship as a sort of katechon—a force to restrain anarchy (or the Antichrist in theological terms)—while entirely overlooking the restorative dimension of Donoso's project.

It is all the more surprising that Schmitt, a modern thinker, continues to be regarded as a traditional-conservative figure, despite his political realism, which inherits from Machiavelli and Hobbes, thinkers associated with the raison d'état, a principle consistently rejected by traditional Catholic thought. This tradition has persistently defended natural law and the Aristotelian-Thomistic view of the common good, a perspective that Schmitt, notably, despised.

Nevertheless, the concession to the state, as embraced by both Donoso and Schmitt, has always been unacceptable to Carlism, and, in a certain sense, history has vindicated this stance. Neither Salazar, nor Franco, nor Vichy France succeeded in restoring the societas civilis (a task that, moreover, was inherently unachievable).

To some extent, the conflict between Carlism and dictatorial conservatism finds a parallel within the political Left. In the debates of the First International, Bakunin recognized that the state could never be dialectically appropriated to achieve social revolution. Historical experience has vindicated the anarchist prognosis: the withering away of the state never happened; instead, as evidenced by existing socialisms, the state further bureaucratized, creating vast administrative apparatuses and elevating a managerial class above the proletariat.

This shared insight between anarchists and Carlists largely stems from their status as historical failures. This phenomenon underscores the epistemological advantage of the defeated: both failed in the dialectic of arms but succeeded in the dialectic of ideas. As Reinhart Koselleck asserted, short-term history is written by the victors, but in the long run, it is shaped by the vanquished, who possess a more critical consciousness compared to the teleological innocence of the victors.

After all, the defense of the fueros, the social cornerstone of Carlism, is politically irrelevant both today and in the 20th century: a return to the societas civilis is unattainable.; conservatism, as P. Kondylis argued, has perished along with the aristocracy, the social bearers of Reaction.

Consequently, Miguel Ayuso, the leading figure of contemporary Carlism, finds himself compelled to theoretically adapt and defend the historically anti-Catholic state as a sort of katechon against what he perceives as the disintegrative forces of globalism. This form of “critical defense” of the state is somewhat opportunistic and reflects an acknowledgment of traditionalism's political decline, having been forced to capitulate to forces that have, quite frankly, overwhelmed it.

In reality, the political-linguistic use of the katechon has always been opportunistic, as is often the case with such concepts. Roman legitimacy had to be defended, and thus Rome, despite its previous paganism, was regarded as an ordering principle in its imperial role against anarchy (i.e., the Antichrist in theologico-political terms). Subsequently, the Church employed this concept to justify the continuity between the Roman world and Catholicism, legitimizing its primacy over the East and defending itself during the Counter-Reformation against Protestant criticisms that equated Rome with the Whore of Babylon.

Yet, despite Ayuso’s opportunism, his position, grounded in Carlism, is significantly more substantive than those who attempt to view the contemporary administrative state as a conservative and “illiberal” force within a purported “Catholic legal thought.” These individuals fail to recognize that the administrative state is, in reality, a post-liberal political organization and, even more critically, they completely disregard the historical lineage of traditionalist political thought to which they claim to be heirs.

However, this debate remains peripheral; the conceptually weak Catholic post-liberal fever was short-lived, despite the vice-presidential candidacy of an opportunist like JD Vance, who seems to be on friendly terms with both God and the Devil. He aligns himself with the Catholic post-liberal craze and the elitist sphere of a spiritually Asian and derivative blogger. The traditional alignment of the Throne and the Altar, the foundation of traditional European society, is fundamentally incompatible with the contemporary Leviathan, not to mention the usurious financial sector and the vapid tech industry.

With all this in mind, I would like to conclude this brief piece by asserting that, despite a certain admiration for Evola (which, aside from the Carlist’s subjective inclinations, can be attributed to strategic reasons: during Operation Gladio in Italy, both traditional Catholicism and paganism faced a common enemy in communism), De Tejada clearly delineates the fundamental discontinuity between the two forms of traditionalism and Evola's interpretative errors. Notably, De Tejada criticizes Evola’s notion of Tradition as being aligned with Schelling’s philosophy of religion (a thinker who was unmistakably modern). In other words, Evola's traditionalism, rather than being a genuine traditional stance, is essentially a variant of modernism.

Let the reader consider this information to determine who is correct, though, ultimately, such judgments will always be a matter taste.

(All footnotes and images in this text are my own and primarily consist of biographical clarifications and translations. Readers can view the original footnotes and images here.)

Remarks regarding Hispanic Traditionalism

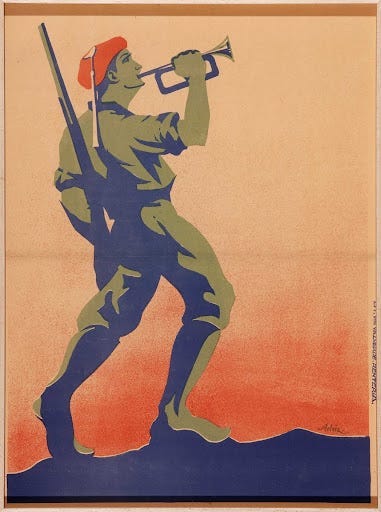

Since 1968, Julius Evola, after enduring years of undeserved obscurity, has gradually risen to prominence within intellectual circles, particularly in the realm of "Traditionalism." Beginning in the 1940s, he emerges as the intellectual figurehead of a distinctive Italian ideological movement, one that—barely forty years old—has embraced both magic and the exaltation of Tradition as its core tenets. However, what Evola introduced as a novel concept in Italy was already the lifeblood of countless men in Hispanic lands, who, under the banner of Tradition, fought with both arms and intellect in service to the cause—none more notably than the Spanish Carlists.

Therefore, as a Hispanic Carlist—and thus a genuine traditionalist—I find it both necessary and worthwhile to examine the towering figure of Julius Evola, giving due respect to the remarkable character he embodies. Yet, this respect does not preclude a critical analysis of his work; rather, it demands it. I will, therefore, scrutinize his contributions with a discerning eye, offering commendation where it is merited, while also addressing those elements that warrant critique.

It is with a measured sense of pride, rooted in the doctrinal purity of my unwavering militant Carlism, that I recognize myself as the sole Spanish scholar to have engaged with the formidable figure of Julius Evola—a point highlighted by Gabriele Fergola1 in his study, "Evola e il tradizionalismo spagnolo." In the prologue to "La Tradizione italiana," included in the Tuscan edition of my work, "La Monarchia tradizionale," I acknowledged the significance of what I termed the "portentous Evolian construction," and conferred upon him the title of "grand maestro." However, this recognition was accompanied by a necessary caveat, reflecting the reservations that his works inevitably provoke in the eyes of a genuine Hispanic traditionalist, as all Carlists inherently are.

My meticulous engagement with Italian culture—an endeavor regrettably rare in our time—combined with the pervasive misperceptions that, even among the most learned, often color the understanding of Hispanic realities from a foreign perspective, has compelled me to discern what is frequently overlooked from Italian soil. Namely, that many whom Gabriele Fergola labels as authentic traditionalists are, in truth, anything but. While they may occasionally invoke this sacred term, it is a disservice to true traditionalism to grant them refuge under its venerable banner.

When examining Evola through the lens of Spanish Traditionalism, it becomes essential to first reject the framework proposed by Fergola in his otherwise commendable and previously cited work. Fergola’s categorization of Hispanic traditionalists includes figures such as Juan Donoso Cortés, Jaime Balmes, Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo, Ramiro de Maeztu, and, among the living, Vicente Marrero Suárez. Yet, his selection notably overlooks significant figures central to the tradition, such as Magín Ferrer, Gabino Tejado, the two Nocedals, Antonio Aparisi y Guijarro, or Enrique Gil y Robles. Furthermore, among contemporary thinkers, the absence of names like Francisco Puy Muñoz, Rafael Gambra, Manuel Fernández Escalante, Wladimiro Lamsdorf-Galagane, Antonio Pérez Luño, José Iturmendi, or Joaquín García de la Concha reduces what should be a robust list to a mere handful of names, thus failing to fully capture the breadth and depth of Spanish Traditionalism.2

The classification of Jaime Balmes3 as a traditionalist is, in fact, a matter of contention, given that he essentially foreshadows the era of subservient Vaticanist Christian democracy that we are regrettably enduring today. Juan Donoso Cortés4, by contrast, was never a genuine theorist of Tradition. His focus lay on commissarial dictatorships and palliative measures designed to stave off crises—responses that, while perhaps pragmatic, were never intrinsic to the healthy and serene essence of Tradition. As for Menéndez y Pelayo5 , though he unearthed traditionalist texts within literature, his approach lacked any intention of engaging with them through a political lens. Ramiro de Maeztu6, meanwhile, engaged with Traditionalism through an Anglo-Saxon perspective, thereby failing to grasp the critical importance of legitimacy—an indispensable criterion in defining true Tradition.

Regarding Vicente Marrero7, an old and dear friend, despite our close relationship, it must be acknowledged that he adheres to criteria that stray from the authentic essence of Spanish Tradition. In Spain, there exists only one true Traditionalism: Carlism, with its centuries-long history of battles and thinkers. By presenting the landscape of Spanish traditionalists as Fergola does, a misleading picture is painted for Italian readers—one that must be corrected before exploring the analysis of Julius Evola through the lens of Spanish Traditionalism.

Given that Carlism is our sole true Tradition, it is indeed surprising that Fergola could make such errors, even while acknowledging and asserting that "the stream of Spanish Traditionalism is diverse," particularly in relation to Evola's stance. This diversity, however, is rooted in a Tradition that remains vibrant and active, especially in regions like Navarre. In a certain sense, one might argue that Evola has not been translated into Spanish because, quite simply, we Spaniards had no need for him. There was "no void to fill, neither historically nor, above all, culturally."

If there was no void to fill, it is solely because Carlism occupied that space, standing as the true embodiment of Tradition. Neither Balmes, Donoso, Menéndez y Pelayo, Maeztu, nor Marrero could ever fill that role. They failed to grasp what Fergola considers the essence of Tradition—such as the profound significance of the "Fueros"—and they lacked any real connection with the legitimate dynasty that, from Charles V to Alphonso Charles I, steadfastly defended local liberties against the abstract notions of liberty championed by the revolution. In Spain, if Traditionalism is considered a comprehensive school and if its ideas are seen as "concrete and historically operative," it is entirely due to Carlism. Not the fleetingly praised liberal dictatorial petit generals admired by Donoso, nor the belated and misguided guelfism of Jaime Balmes, nor the remedial approach of "L'Action française," as echoed in the Spanish Action of Ramiro de Maeztu, can claim such a distinction.

To emphasize this point, when a Carlist aligns with the usurper dynasty spanning from the so-called Isabella II to the so-called Alphonso XIII, they cease to be a traditionalist. Examples include Alejandro Pidal8 at the turn of the 19th century or bourgeois capitalists in the mold of merchants like Antonio Oriol9 in contemporary times, who joined a political party—the conservative party—contrary to the principles of the Spanish Tradition, which rejects such affiliations. This act results in the legal rupture of Catholic unity, the fundamental norm of Hispanic Tradition.

These clarifications are crucial for the reader to understand the criteria used in evaluating the figure of Julius Evola in this study. Another important correction pertains to Gabriele Fergola's mistake in attributing a "Catholic orientation, if not even guelph," to me and, by extension, to the Carlism I represent ideologically here.

Carlists draw their raison d'être from their role as steadfast guardians of the legacy of Philip II, the Council of Trent, and the Counter-Reformation. This heritage, which we uphold with a chivalric devotion, forms the bedrock of our beliefs. The true worth of the legitimate monarchs who defended Tradition in the 19th century is found in their continuation of the golden lineage of the Spains10, who surpassed even the papacy in their zealous defense of Christendom against papal errors. Our Catholic exemplars include the King of Naples and Emperor Charles V, who imprisoned Pope Clement in Sant' Angelo, and King Philip II of Sardinia, who detained bishops in Naples—actions taken in divine service even when the papacy acted against the universal reign of Christ. In holding the popes accountable politically, none can match our kings from the two peninsulas.

It is imperative to underscore that we are Catholics, not Vaticanists. This profound distinction separates our Catholicism from the modern Guelphs found in today’s Christian democracies.

With these clarifications, the reader is now positioned to determine whether we grasp the profound work of Julius Evola.

A Kshatriya of the West

Julius Evola transcends both his era and his contemporaries. Born on May 19, 1898, he now inhabits the realm of immortality. He has shed the trappings that bind the ordinary: academic accolades, family ties, and the pursuit of intellectual validation from others. When Gaspare Cannizo notified him of Enrico Crispolti’s11 examination of his work in "Il mito della macchina ed altri temi del futurismo," Evola remained unmoved by the tribute. Residing in solitude with his self-styled "baron" status, he stood aloof from the passions and judgments of his time—an "irreducible aristocrat," as Sigfrido Bartolini aptly described, perpetuating the legacy of the true aristocrats of spirit.

Giovanni Volpe and Adriano Romualdi affirm that Evola showed no inclination towards gathering or dismissing followers, nor did he seek to establish a school of thought. His unwavering moral discipline placed him beyond the reach of adulation and impervious to contempt. He journeyed through life with the serene detachment of silent mountains, untouched by the triviality of mortal concerns. He epitomized nobility in its purest form.

Thus, any evaluation must focus solely on his ideas and work, not on the man himself. Criticism or praise, while they might attempt to touch his essence, would leave him unmoved, ensconced in the granite solitude he deliberately chose for his life. Julius Evola, as a person, remained an enigma—perhaps saint-like, certainly sacred-like. He carried an immense sacredness akin to the reverence religious societies bestow upon extraordinary beings, those who transcend ordinary humanity and embody the majestic exceptionality of incomprehensible figures.

Julius Evola transcends the ordinary and the mundane conflicts of daily existence. He cloaked himself behind his books, purposefully dissolving his personal identity within the framework of his ideas. This method allowed him to remain captivatingly veiled in mystery—a mystery that has forever been the hallmark of the sacred.

Julius Evola's essence diverges from the divine Brahman, the ethereal twin of the gods manifesting in flesh and blood. Instead, his temperament aligns more with the kshatriya's call to action than with the karmic incarnations of the divine. His journey followed the "karma-marga," the path of deeds. Whatever he accomplished—likely a scope forever beyond complete revelation—was attained through the kshatriya-karma, where nothing was handed down without relentless endeavor.

Boris de Rachewiltz's assessment in Uno kshatriya nell’Età del Lupe misses the mark when attributing Evola's kshatriya nature solely to the stark superiority of his unyielding indifference. Rachewiltz suggests that Evola "revives his kshatriya essence, marked by an unflinching disregard for compromise and an absolute detachment from human judgment." However, in Il cammino del cinabro, where Evola self-designates as a kshatriya, he is careful to clarify that this identity does not equate him to a brahman.

"The second disposition could be called - to use a Hindu term - of kshatriya. This word in India designates a type of human inclined to action and affirmation, 'warrior' in the strict sense, opposed to the religious, priestly, or contemplative nature of the brahman. This has also been my orientation, although it has only been specified in the right way little by little".

Julius Evola is defined by action, not contemplation. His disregard for others reflects not a divine detachment but a dynamic and fervent pursuit of the divine. This impassivity is a manifestation of his inner vibrancy and active drive. In Il cammino del cinabro, Evola openly acknowledges his kshatriya nature, explaining that it compelled him to act without being swayed by the notions of success or failure. He further asserts that, as a kshatriya, his drive was to "assert himself in the domain of action."

Julius Evola engages in his work with the intention of making a profound impact, even though he remains indifferent to the outcomes. He is not the contemplative mystic lost in divine rapture; instead, he is the warrior waging a battle for the sacred in a desacralized world. His relentless struggle persists, even if, in his majestic solitude, it seems he has little concern for projecting his message. Nevertheless, he was destined to be the bearer of this message.

In yogic terminology, Julius Evola could be described as a "siddha," transcending both gods and men, or at the very least, a "vira" in the context of left-hand tantrism—embodying the kshatriya with boldness, audacity, and unyielding superiority. This characterization is essential for understanding his true essence. Without this framework, Julius Evola's personality remains enigmatic. Thus, when examining the works of such a figure, the initial task is to unravel the true nature of the subject at hand.

The truth is, Julius Evola doesn't merely disdain the world; he aspires to dominate it. His most revealing portrayal emerges from the symbolic verses embedded in the sexual symbolism of the Indian East—a realm from which he drew the fundamental principles for his actions, thoughts, and existence. Evola's work is driven not merely by a desire for control but by a quest to transcend the world itself.

In the poem "Astrid," Julius Evola transcends the mere contemplation of the feminine as passive beauty. Instead, he elevates it to a sacred plane through the act of possessing Astrid. In that moment, Astrid is transformed into the embodiment of the eternal and sublime feminine. Against the backdrop of the chaotic city’s black and yellow horizon, the sacramental act of possessing her encapsulates the entirety of Evola’s being:

(Here's a translation of the poem, attempting to maintain the rhythm and poetic quality)

He had stopped his car,

which, inside, suffocating,

with intoxicating sandalwood, applauds him.

In a gloomy suburb

under a slow rain

the coal wagons pass;

the fog blurred the distances,

the solitudes

and the melancholies with a yellowish rhythm.

And he had broken the spell.

His ambiguous gaze,

whirlwind,

the dizzying transparency of his stockings,

the lace’s foam,

his legs which,

illuminated,

spread apart;

the inverted and open idol,

my being immersed in you

sunk in a burning darkness

endless,

his brief cry

green dilation

dissolution.

Are you Astrid?

Astrid with the high white forehead

seal of domination that cuts

with the immense city

black and low

on the great zinc plate of the sky.12

These verses, composed in his youth, do not manifest the unrestrained desire of "raga-klesha" found in yoga. Rather, they embody "maithuna," aligned with the superior condition of the "vira." This represents the universal sacralization of existence, a perspective reserved for the initiated. The exceptional qualities of Evola's behavior—his calm demeanor and detachment from the general public—are encapsulated within this youthful poem to Astrid.

Here, despite being a product of the twentieth century, Julius Evola aligns himself with an ancient race that once possessed a transcendent spirituality, comparable to the divine—a notion he explores in Il mistero del santo Graal. From this elevated vantage point, Evola observes contemporary society, witnessing its decline as it approaches its final dissolution. Consequently, he envisions a salvific belief: as the current cycle concludes, the eternal forces of Shakti—the universe's creative energy—will usher in the next cosmic cycle through these superior individuals. This is how Julius Evola perceives himself or, at least, believes himself to be.

Commonalities

From these exalted heights, Evola meticulously constructs his metaphysical framework—or, as I interpret it, his philosophy of history. This central theme is masterfully explored in his seminal work, Rivolta contro il mondo moderno, which is anchored in the doctrine of the four ages. Evola begins with a primordial era of gods, a period that transcends mere historical context and explores the metaphysical realm. In this epoch, superhuman entities embodied a reality where the mundane and the transcendent were indistinguishably intertwined. During this sacred time, the foundations of a normative code, a political system, and a compendium of esoteric knowledge—collectively referred to by Evola as Tradition—were meticulously established.

It transcends the conventional notion of prehistory as defined by historians and stands apart from the lifestyle of present-day primitive societies. This remarkable civilization exists within a qualitative dimension of time and space that is more metahistorical than prehistorical or proto-historical. It cannot be equated with the existence or mentality of today's under-civilized peoples, for what these contemporary groups practice represents a degradation of higher forms rather than an authentic pre-civilized way of life.

From the lofty vantage of this perfect society, Evola delivers a critique of our contemporary world with unparalleled acuity, offering insights that merit the highest praise. He asserts that we are entrenched in the fourth stage of decay. After the ages of gold, silver, and iron, we now navigate the era of the wolf from Norse sagas, the dark age or "kali-yuga" of Hindu tradition, the age of iron from Iranian lore, and the age of clay foreseen in the Book of Daniel. The divine epoch of the gods has transitioned through the stages of priests and heroes, leading to the age of merchants marked by the triumph of the "Tiers état" in 1789, and subsequently, the proletarian era ushered in by communism in 1917. The sudra caste is poised to replace the vaishya, following the fall of the kshatriyas and brahmins.

In "Cavalcare la tigre," Evola meticulously dissects the myriad factors that have dismantled ancient values and traditions. Though this is not the moment to revisit his masterful critiques, his insightful connections between concepts, and his incisive rebuttals of progressivism, liberalism, and democracy, it is crucial to highlight the depth of his observations. Evola addresses the crisis of the family, the desacralization of thrones, the progressive desacralization of the cosmos, the fragile pretense of mathematized science, the materialist dominance in the economic realm, and the failures of rulers who, though capable of embracing traditionalism, have conspicuously failed to do so. In this critical domain, alignment with Evola's perspectives is essential. Any objections stemming from the ideological inclinations of Hispanic Traditionalism should only serve to underscore his arguments with greater force.

The depth of agreement with Evola's critique is so striking that I must highlight his incisive observations on fascist cultural politics. This reflection provides Spanish readers with a mirror to our own circumstances, shedding light on how Franco, despite his victory in the field of arms, failed to secure an intellectual triumph. Evola's comments on Benito Mussolini in the 1930s apply directly to the Spain that was born on July 18th, only to suffer a cultural stifling. The so-called "revolution" in the cultural sphere was a mere facade. To embody "fascist culture," one needed only to be a party member and pay token homage to the Duce. Beyond this, substance was irrelevant. Instead of forging a new path, rejecting established norms, and subjecting everything to a thorough overhaul, fascism displayed a provincial and "parvenu" ambition: to attract the "exponents of existing bourgeois culture," provided they offered only formal and superficial allegiance to the regime.

Thus, the desolate spectacle unfolded: an Academy of Italy populated predominantly by agnostic or anti-fascist members in their private convictions. This was true even for numerous esteemed individuals, institutions of fascist culture, and leading publications. Consequently, it is scarcely surprising to encounter many of these figures shifting allegiances in the democratic and anti-fascist Italy of the post-war era.

Despite the inevitable doctrinal divergences between Evola's perspective and our own as Hispanic Traditionalists, there exists a profound unity in our shared repudiation of the modern world. Our gratitude towards Evola remains unwavering for his incisive and profound critique. Amidst the dismal landscape of intellectual betrayals in Italy and Spain, Evola emerges as the valiant knight, steadfastly allied with us in the monumental struggle against the pernicious effects of bourgeois corruption and the degenerate cowardice that epitomize the decayed West of today.

Having conveyed these high praises for Evola, an intellectual leader who, despite his disdain for such a role, commands significant respect, it is now crucial to address the divergences between us. This is done with the intention of laying the groundwork for a fruitful dialogue among his followers—a preliminary step toward collaborative action for those committed to resisting the dark, diabolical forces that undermine the traditional meaning of existence, primarily within the Catholic Church and secondarily across the Western world. These remarks are made with the aim of fostering unity in action. Thus, they are meaningful only to the extent that they clarify positions and enable us to engage in dialogue from a well-defined standpoint—a dialogue that, I hope, will lead to the brotherhood I ardently wish for, with all the fervor and dedication I can muster.

The Concept of the Divine

Hispanic traditionalist thought is grounded in the profound dualism between the Creator and the creature, highlighting the divine norms to which human conduct must conform. In this framework, religion functions as a binding force, integrating and subordinating the human ego to the transcendent divine Ego through a logical and non-arbitrary process—arbitrariness being an inconceivable imperfection in the divine nature. The incarnation of God in the second Person of the Holy Trinity, Christ, introduced a doctrine that compels human freedom, uniting individuals through the principle of Love. This principle, far from offering comforts or accommodations, demands a rigorous alignment with divine will.

Christ desired a robust, unyielding religiosity, one that could not be softened or compromised. As stated in Matthew 10:34, “Do not think that I have come to bring peace upon the earth. I have come to bring not peace but the sword.” This firmness is further underscored in Matthew 12:30: “Whoever is not with me is against me,” and in Luke 12:51: “Do you think that I have come to establish peace on Earth?” Additionally, Luke 9:39 asserts: “I came into this world for judgment, so that those who do not see might see, and those who do see might become blind.” This depiction of religiosity is knightly, militant, and combative, as demonstrated by Christ’s condemnation of the Pharisees as whitewashed tombs and his physical act of whipping the merchants in the Temple.

In this resolute and military approach to religion, one draws near to God through service, employing both doctrinal and martial means. Christianity, from the traditionalist Hispanic perspective, is fundamentally a service to God guided by the teachings of Christ.

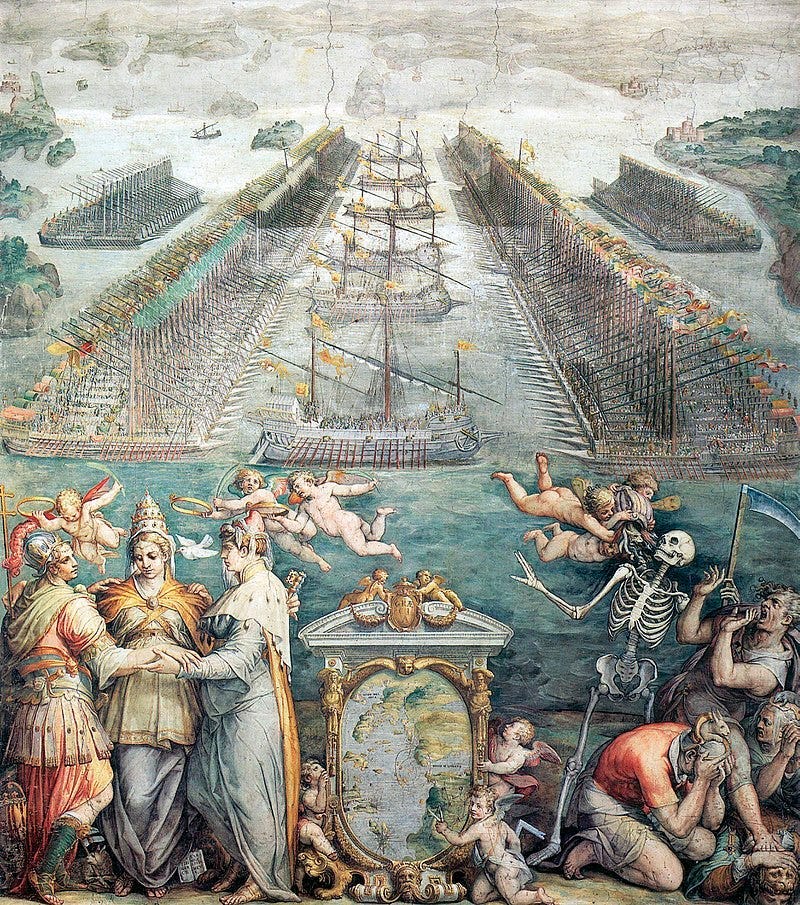

This perspective elucidates the medieval Christian heroic crusades, the eight-century struggle in the Iberian Peninsula, the militant Catholicism of the Counter-Reformation, exemplified by events such as the battles of Mühlberg and Lepanto, Spain's missionary endeavors, and Carlism as the divine war against the frail petit-Spain of the 19th century. The heroic form of the Tradition of the Spains involves reaching God through the militia.

Conversely, Evola's path to the divine diverges markedly, seeking not through martial engagement but through fusion. His religious experience aligns with Hinduism, marked by the perception of nature as the central reality or "darshan." As articulated by Sir Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan in The Hindu View of Life, this experience is not merely an emotional upheaval or subjective fantasy but a holistic integration of the self into the fundamental reality. It is an affirmation of the divine through the cultivation and realization of divine energies within man.

In their approach to God, the men of the Hispanic Tradition undertook a heroic act, acknowledging themselves as instruments of God on Earth. Beyond the individual religiosity inherent in Christianity, where each person bears exclusive responsibility before God for their earthly actions, they perceived their mission as a knightly service. Faith, for them, was a knightly mission.

The Spains preserved the heroic spirit of medieval Christianity by maintaining the militant Christianity of the medieval era. Hildalguía was both a militia and an armed mission. A significant failure of Julius Evola, which is central to our disagreements, lies in his neglect of the knightly sense of the Counter-Reformation. This oversight undermines his entire conception of history as supreme heroism.

Concerning the approach to God, Evola favored the Hindu life of left-handed tantrism. His aristocratic nature as an innate kshatriya, captivated by the spectacle of the "Shakti," the wife of various gods and the unique universal potency expressed in each form of life, led him to infuse tantrism into Western contexts. As explicitly stated in Il cammino del cinabro:

"My purpose was to translate into terms of speculative thought those foundations of the Eastern system that were not derived from speculation but from spiritual experiences and expressed through images and symbols."

Only in this way, he said, could the East have acted creatively on the West.

Contrary to what many may deduce from his writings, Evola does not deny the dualism between the Creator and the creature. The central scheme of Hindu philosophies precisely involves alternating between the “Shakti,” or universal potency, and the “Maya,” the apparent reality of things and beings. The “leela” or cosmic play is a veil that the initiated can pierce to achieve union with the divine identity. The difference lies in the fact that, unlike Christianity, it is not a matter of invoking God but of realizing this God within ourselves.

The realization of the superhumanized subject, made the "pitha" or the seat of the universal "Shakti," can be achieved in two ways: through asceticism, as found in Vedic or Buddhist traditions, or by awakening the dormant potentialities in the human body through the use of specific "mantras." This process leads to the activation of the "kundalini," the dormant serpent coiled at the base of the spine in the "muladhara."

It ascends through the "sushumna," the spiritual channel believed to run along the spine, passing through each lotus or “padma,” until it reaches the “sahasrara,” the multicolored thousand-petaled lotus at the top of the head. Here, the fusion of the individual with the universal, of the human with the divine, occurs—a supreme state for the initiate, transcending the constraints that bind the "pashu" or common men. By embodying the divine, every action of this superman—now a vessel of the divine—becomes pure and upright.

In this context, the sexual act, the "maithuna," acquires the significance of a religious ritual, representing the most reliable means to dissolve individual consciousness. The feminine "yoni" transforms into an altar, not merely an instrument of pleasure—a sacred space for a mystical rite, rather than a source of indulgence. As Paul Masson-Oursel states in Le Yoga: “le çaktisme est ferveur, non débauche.”13

In left-hand tantrism, the attainment of the divine is achieved through the exaltation, rather than the suppression, of sacred shaktic energies within the human body. This vibrant, heroic approach of tantrism contrasts sharply with the austere philosophies of Jainism or Samkhya, embodying a form of kshatriya religiosity in Hinduism that parallels the more ascetic brahmana approach.

The kshatriya quality of tantrism elucidates Evola's preferences and his partial embrace of Hindu thought as a remedy for the West's malaise. What puzzles me is his reliance on the East to unearth a heroic sense of life. Perhaps his disorientation was influenced by his readings of Nietzsche, which provided him with a distorted and skewed interpretation of Christianity as a religion of slaves and cowards.

Throughout Evola's entire body of work, a significant oversight is evident from the outset: the belief that the heroic sense of Christianity ended with the Ghibellines, failing to acknowledge its persistence through the Counter-Reformation. In this period, the grand Christendom of the Empire transformed into the minor Christendom of Spain to survive. Had Evola recognized this, he would have discovered in the West the fulfillment of his aspirations as an aristocrat of both blood and spirit, without the need to turn to the universal formulas of left-hand tantrism, which ultimately undermined his role as a kshatriya.

By reducing religiosity to a historically specific personal phenomenon, Evola limited his ability to confront the universal and combative dimensions of the ills plaguing the twentieth century. Rather than retreating indifferently into his ivory tower, he could have embraced the role of the militia that his status as a knight demanded.

Evola's error lay in his persistent attempt to be a kshatriya despite being a knight. By doing so, he relinquished the intellectual leadership that his merits warranted, confining himself to the futile personal pursuit of an incomparable superiority—one that was inaccessible to others. This leadership role was his duty in the somber times in which we live.

In response to the West’s crisis and its quest for salvation, Evola sought to offer a remedy through the naturalistic mysticism of tantric yoga. This approach parallels that of S. Radhakrishnan in his work Eastern Religions and Western Thought, where he presented a formula of ascetic mysticism. Notably, both Radhakrishnan and Evola developed their theses around the same period, with Radhakrishnan in 1933 and Evola in 1934.

Despite this, both solutions appear inadequate, given the substantial differences between Westerners and the diverse philosophical systems of India. This inclination to seek salvific spiritualisms in the East mirrors historical patterns, such as the Roman Empire's tendency to turn to the cults of Mithra, Baal, Isis, and the magi during its spiritual and institutional crisis in the transition from the Republic to the Empire.

The Idea of Tradition

The concept of Tradition is markedly different between Evola and Hispanic traditionalists.

For Evola, Tradition and religiosity transcend historical boundaries. They embody systematic and undeniable truths, existing in their pure form rather than through historical development. These truths are revealed, not acquired through knowledge; they are grasped “when one is capable of viewing from that non-human perspective, which is identical to the traditional perspective.” Tradition, for Evola, exists outside of history—not because it precedes it in time, but because traditional time, unlike chronological time, is not a mere sequence of facts. It is not measured by moments but is a qualitatively distinct, metaphysical reality, fundamentally estranged from historical progression.

The essence of Tradition is situated in a superhuman realm, beyond the reach of historical constraints, as history itself remains a strictly human construct. This essence eludes the grasp of intellect and serves as an ideal model forever beyond full attainment. There are higher-order realities, archetypes, which may be obscured by symbols or myths. These archetypes might or might not be reflected in institutions or historical facts—elements that are always intrinsically human.

In such cases, there is an intersection between supra-historical Tradition and its historical manifestation, with myths serving as the conduit. The myth, therefore, is the foundational element and should be regarded as the starting point. Representing the expression of traditional content from beyond, the myth encapsulates an invisible reality that is as tangible as historical reality itself. The myth signifies the integration of the superhuman into the human, bridging Tradition from its metaphysical realm into the temporal and spatial confines of historical reality.

Beneath the intricate web of myths lies the metahistorical Tradition. For Evola, this Tradition is fundamentally unitary—a universal and exemplary archetype that projects itself into specific historical realities.

To uncover this profoundly distant qualitative Tradition, one must explore the substratum of myths. Myths serve as the conduit to ascend to the knowledge of this singular Tradition, functioning as the source of historical reality through their parallel correspondence in certain historical contexts. This unique and exclusive Tradition, which can be found in various forms across all peoples, is revealed through its manifestation in these mythic expressions.

Preferably, this exploration would take place in India. Julius Evola's ideas are not entirely novel but rather echo concepts prevalent in German idealism. For near-literal precedents of Evola’s theses, one should examine the symbolic significance Novalis attributed to Indian music, as detailed in Susanne Sommerfeld’s Indienschau und Indiendeutung romantischer Philosophen. Additionally, Schelling’s views on the interpretative autonomy of myths—expressed as der Mythos deutet sich durch sich selbst—and his perspective on yoga as a path to union with Transcendence, further illuminate these connections.

Consider Hegel, who posits that Hindu philosophy culminates in the realization of the unity between man and universal Substance. Alternatively, examine Schopenhauer’s reduction of the dominant force, the ‘Shakti’—or eternal energy of the universe.

Evola’s reliance on Schelling is particularly evident. One cannot fully grasp Evola's metaphysics without recognizing his distinction between the exoteric form and esoteric content of myths, a distinction Schelling made in Über Mythen, historische Sagen und Philosopheme der ältesten Welt. Evola’s characterization of Tradition as a philosophical myth, in contrast to historical myths, mirrors Schelling’s distinction between the philosophical myth as a universal rule and the historical myth as a transmission within a particular people.

The sole innovation Evola introduces in relation to Schelling’s thought is terminological. Whereas Schelling refers to the philosophical myth, Evola speaks of the unique metahistorical Tradition. Similarly, while Schelling addresses the historical myth, Evola discusses the projections of Tradition into historical time.

In Evola's terminology, the two sections of Rivolta contro il mondo moderno are titled Il mondo della Tradizione and Genesi e volto del mondo moderno. Schelling would have conveyed the same ideas, referring to Tradition as a philosophical myth and historical Tradition as a historical myth. Additionally, Schelling discusses the sacred nature of historical Tradition when it manifests within a specific people as the philosophical Tradition or myth: "Tradition ist es also, was Lehre, Glauben und Sitten eines jeden Volks heiligt,"14 found in Über Mythen from 1793. Remarkably, Evola does not even mention Schelling!

More of a difference is Schelling's attempt to find a commonality in all myths that converges toward a primordial religion, while Evola seeks a unique and supreme Tradition.15 For Evola, this Tradition serves as a divine archetype. The distinction lies in Schelling’s Christian approach, which seeks the divine through intellectual means, whereas Evola, as a left-hand tantrist, seeks to merge with the divine through the natural processes of tantric initiation.

In 1948, Aldous Huxley, in The Perennial Philosophy, sought to navigate a middle path, valuing the primordial philosophia perennis as the essence and core of all religions. That same year, Frithjof Schuon, in De L'unité transcendente des religions, broadly integrated Christ with the Hindu Kalki-Avatara and the Bodhisattva-Maitreya, presenting them as manifestations of the singular, original Tradition. Ultimately, it’s a matter of taste: all these approaches strive toward the same goal—a sacred knowledge that precedes and surpasses history, discovered through its manifestations in human actions that shape historical development.

The mediating element is the person who embodies divinity: Christ in Christianity, various gods in Hinduism, Gautama in Buddhism, Evola, and those who attain sublimation in Tantrism. This concept is not new, as it resonates with what Helena Blavatsky aimed to convey in The Secret Doctrine (1890), what Arthur Arnould proposed in Les croyances fondamentales du Bouddhisme (1895), what Rudolf Steiner explored in El misterio cristiano y los misterios antiguos, and what Edouard Schuré discussed in L'évolution divine: Du Sphinx au Christ (1912).

To avoid listing additional precedents for these syncretic essays based on myths and symbols, which are seen as reflections of a singular sacred Tradition, one need only consider Henri de Lubac's La rencontre du bouddhisme et de l'Occident to appreciate the extent of influences on Evola’s views around 1900. Despite this, Lubac, writing in 1952, does not mention Evola, even though La Rivolta had been published in 1934.

The failure of such claims lies in the fact that transferring Tradition from the plane of meta-historical myth to historical reality is always mediated by purely subjective criteria. Even Evola himself acknowledges that moving from a higher plane to the realm of human events involves a difficult and perilous shift in perspectives. "The shift from considering Tradition as supra-history entails a mutation of perspectives." These perspectives are inherently subjective, leading to unavoidable errors due to their dependence on the author’s cultural context.

The shortcomings of Evola's work stem from his subjectivism in interpreting the transfer from meta-historical Tradition to its embodiments in specific historical moments. He concentrates on tantrism, Rome, the Graal, the alchemical 'La tradizione ermetica,' the medieval 'Fedeli d'Amore,' the Ghibelline emperors, and the Rosicrucians. However, he overlooks the Spain(s) of the Counter-Reformation, which arguably embodied traditional values to a greater extent than the other examples he considered.

In contrast, for Hispanic traditionalists, Tradition is not external to history but rather a synthesis of metaphysics and historical reality. As Christians, Spanish traditionalists uphold a belief in theological equality before God, affirming the universal capacity for salvation for all humans. Following Saint Thomas Aquinas, they view each individual as embodying an essential metaphysical reality, expressed through a variety of existences. These diverse existences contribute to the concrete heritage of Tradition, in stark opposition to the abstract notion of man found in Protestant and revolutionary ideologies.

For us, man is a metaphysical being who inevitably shapes history from birth, as he is born into a realm of concrete realities, which is precisely the inherited Tradition. Evola translates the metaphysical into the present plane, but he does so by applying the notion of 'karma' as a natural condition reflecting a higher, underlying reality. In this way, he can assert that man is concrete because he achieves perfection by fully realizing his own nature.

In tantrism, 'karma' refers to the evolving actions of the body, dictated by caste or the transcendence of caste through the attainment of 'siddhu.' Thus, the realm of the concrete is reserved for the 'pashu,' or common man, bound by the inevitability of nature. This rigidity contrasts sharply with Thomism, which differentiates between the metaphysical essence of being and its historical manifestations. In the Catholic Hispanic Tradition, the traditional man is born into history with the potential to shape it, while Hindu thought confines him to the rigid constraints of birth and the unyielding force of castes.

Anchored in history, Tradition is necessarily a free action according to the Thomist anthropological conception, which views Tradition as a metaphysical force shaping history. In contrast, for Evola, 'natura propria' equates to 'dharma,' representing the inherent law of being. It is this 'dharma' that defines the specific situation of each individual, but according to a meta-historical legislation embedded in the inevitability of caste, rather than in the Christian notion of freedom. As stated in La Rivolta:

"In fact 'dharma' in Sanskrit also means one's own nature, the inherent law of a being; its exact reference, in reality, belongs to that primordial legislation, which hierarchically orders, in line with justice and truth, each function and form of life based on the inherent nature of each one."

Here, the orientalizing error of tantrism, adopted by Evola, becomes apparent: it views man as possessing a nature that embodies divine possibilities but fails to distinguish between the metaphysical, natural, and historical planes. Evola's superhuman Tradition is seen as manifesting in the physical nature of man, yet it does not account for the freedom that Christians attribute to human nature.

In essence, Evola's inability to grasp Tradition stems from his concept of man, which obstructs his understanding of history. Consequently, what he refers to as Tradition remains distant from the activities of peoples, viewed merely as a possibility for privileged or initiated beings. This perspective excludes the men who shape history, from whose refinement Tradition is born for us. Such an ahistorical Tradition bears no resemblance to what we, as Spanish traditionalists, understand as Tradition.

Evola thus conflates the disdain for democracy, which Spanish Carlists share to an equal or greater degree, with the theological equality of men, all while preserving their natural, existential, and concrete historical diversities. We will revisit this issue when exploring the reasons behind his misunderstanding of natural law.

Of course, Evola's stance is as inconceivable as the one taken by the Ceylonese Buddhist Church in The Revolt in the Temple, an official publication commemorating the 2500th anniversary of Buddha. This stance imports Anglo-Saxon freedoms into Buddhism, overlooking the essential theological freedom that should be the doctrinal core of Buddhism. Such excesses can be extremely dangerous.

We, the Carlists, uphold a Tradition shaped by our ancestors, not merely an unverifiable myth. Our Tradition is vibrant because it is not confined to extrahistorical notions but is actively realized through human action, inevitably creating history. Nevertheless, it is not relativistic, as the free actions of man are always within the framework of his metaphysical condition as a creature bound by the laws set by God—both explicitly in revelation and implicitly in natural law.

Otherwise, it would be reduced to one of two things: either the unverifiable foundation of myths, whose purity cannot be guaranteed due to their transmission by fallible men, or the arbitrary whims of imperfect and limited beings. History within natural law, human action guided by divine laws, and natural freedom within the cosmic natural order—both physical and ethical—are the sources of Tradition as understood by Spanish traditionalists.

It is regrettable that our premises do not align, despite our agreement on the consequences. While he explores remote tantrism, he misses the opportunity to explore the Christian classics of Spain. With his powerful intellect, he could have illuminated and enriched even one of these seminal works.

Militant Christianity

In these considerations, Evola's disdain for Christianity becomes evident, as he perceives it as a denial of the integral Tradition. He believes he is part of a metaphysical tradition where man achieves realization through tantric initiation, while the realization of the Christian occurs on what he terms a "mystical-devotional plane" in Maschera e volto dello spiritualismo contemporaneo.

It is a clash of mentalities on two fronts. Firstly, the assertion that Christ's message possesses universal and exclusive validity directly contradicts the tantric view of achieving divinity through yogic initiation exercises. Evola simply notes his repugnance without offering justification in La Rivolta when he writes that

"Jesus Christ represents a fundamental challenge to the traditional integration we are discussing. The idea that His person, mission, and message of salvation possess a unique and decisive character in universal history—evident in the exclusivist claim of Catholicism—poses a significant obstacle. This is especially noteworthy given that this notion constitutes the first article of faith for Christianity in general."

Evola doesn't even attempt to justify his denial of the exclusivity of Jesus Christ's divinity or explain why rational arguments cannot challenge it. Instead, he counters the act of faith in Christ's divinity with his own act of faith in tantric divinization. This approach is a natural consequence of the conception of divinity discussed earlier. Acts of faith, by their nature, are submissions to what reason cannot fully encompass or comprehend, rendering them beyond the reach of rational debate.

The absurdity lies in Evola’s insistence on submission to his tantric faith and the unprovable chimera of his meta-historical pantheon or tradition, transmitted through dubious esoteric channels, while he outright rejects the Christian faith.

It is a preliminary point of departure where two opposing conceptions of divinity clash. In this realm, Spanish traditionalists place unequivocal faith in the divinity of Jesus Christ over what Evola deems divine. There is no room for approximation here. Our Tradition is Christian, fanatically Christian, to the utmost extent (my italics).

Linked to the above is Evola's perspective on guilt and submission to God, a characteristic of Christian dogma. Influenced by the tantric belief in the possibility of embodying divinity, Evola rejects the submissive stance of the Christian before God and denies the eternal Christian impossibility for the creature to attain divinity in any form.

Evola’s contrast between Germanic-Nordic honor—the essence of imperial Rome—and the Christian concept of universal brotherly love reflects the Rosenbergian dichotomy. This dichotomy emphasizes the differences between Germanic 'Mut' (courage) and 'Selbstbeherrschung' (self-discipline) versus the Christian virtues of "Demut und Liebe" (humility and love).

Both authors present similar arguments: the absurdity of the notion of sin and the denial of salvation. Julius Evola's statements in Chapter X of Part II of Rivolta echo A. Rosenberg's remarks in Chapter I of Book I of Der Mythus des 20. Jahrhunderts. I refrain from further elaboration, as the pain of blasphemy has always irritated me (my italics).

For Hispanic traditionalists, this aspect of Julius Evola's intellectual message, reflecting the most extreme elements of National Socialism, is categorically unacceptable. We Carlists recognize no divinity beyond that of Christ and accept no salvific message other than the Gospel. The divergence is clear: Evola’s interpretation of Christianity starkly contrasts with ours. Like Rosenberg, Evola depicts Christianity as a religion of slaves, marked by abject submission, spiritual timidity, and a degrading resignation.

For us, Christianity embodies the service to the unique God, a front of noble deeds, an aristocracy of life’s values, and a banner of heroic struggle. Perhaps this is because the Germans have never known, as the Hispanics have, the honor and glory of being champions of the Counter-Reformation and subjects of Philip II of Castile, and Philip I of Naples, Sicily, and Sardinia.

Had Evola and his Teutonic predecessors been acquainted with the heroic, armed, and warlike dimension of Christianity, they might have reached different conclusions. They would have grasped that the Christian faith is a missionary struggle, an armed arm in the battles of the Lord.

My grandparents, who were Castilian and Neapolitan, understood the gravity of this struggle and its heroic nature. The vivid demonstration that Tradition manifests in history is this very divergence in perspectives on Christianity, which starkly separates Evola from Spanish traditionalists. Evola’s lack of appreciation for the golden Spains—those lesser-known yet powerful realms of Christendom, an Empire lacking the imperial title but nonetheless fulfilling imperial functions—leads to a profound clash of concepts. He envisions Christianity as a form of spiritual cowardice, while we hold dear the image of Christians who, with the valor of crusaders, have engaged in the Lord's battles with heroic resolve.

The most intriguing facet is that, despite his generally negative stance, Julius Evola aligns with strict Catholicism on certain issues. In L'arco e la clava, for instance, he revisits the term pietas, reestablishing its political dimension and extending its connotation of devotion from parents to the homeland: "Pietas could also manifest itself in the political field—pietas in patriam meant fidelity and due respect to the State and the fatherland."

Similarly, St.Thomas Aquinas explained in the Summa Theologiae, secunda secundae, question 101, article 4 ad tertium:

"Ad tertium dicendum quod pietas se extendit ad patriam secundum quod est nobis quoddam essendi principium."16

Clearly, Saint Thomas Aquinas demonstrates a terminological precision that Evola lacks. Aquinas associates piety with parents and the fatherland, not with the State. This distinction is crucial, as it helps avoid the common error of conflating political power—a necessary ordering factor present in every human group—with the State. The State, as an historical form of political power, originated in Sicily in the latter half of the 14th century, coming into existence only after the Constitutions of Melfi in 1282.

Natural Law

These preceding assumptions lead Evola to concoct an utterly untenable definition of natural law. His version of natural law is a sort of Manichaeism, reminiscent of the scholastic debates from the Jesuit seminars of the Baroque era, and it is easily refutable. Evola's so-called natural law bears no resemblance to its genuine essence. Instead, it represents an arbitrary imposition of meaning on a term that denotes vastly different concepts.

For Evola, natural law is the law of the "pashu," the common man, rather than the law of the superior man—the one possessing Germanic honor or capable of ascending to the divine through Tantric initiation. Enmeshed in the dichotomy between the inorganic nature of Mediterranean mother goddess cults and the Germanic, Aryan, and Nordic ordering principles, he overlooks a fundamental truth: within any natural order, there exists a hierarchy of beings simply because order itself necessitates it.

Thus, Evola writes in L'arco e la clava:

"The form has traditionally signified spirit, and matter has signified nature, the former being linked to the paternal and virile, luminous, and Olympian element (in a sense that remains clear to the reader today), the latter to the feminine, maternal, purely vital element"

Nature is then seen as the formless, the disordered, the egalitarian, while spirit is what imposes order on natural chaos. Evola forgets that any order in nature, by virtue of being order, inherently implies hierarchy. Nature exhibits order because, from the beginning of time, it has been cosmos rather than chaos. Unordered nature would cease to be nature. Saint Augustine splendidly elucidated this in Enarrationes in dinavit creaturas:

"a terra usque ad coelum, a visilibus ad invisibilia, a mortalibus ad inmortalia. Ista contextio creaturae ista ordinatissima pulchritudo, ab imis ad summa concedens, a summis ad ima descendens, nusqueam interrupta, sed dissimilibus temperata, tota laudat Deum."17

The notion of a chaotic nature is merely a fantasy of Julius Evola, straddling the line between the impossible and the inadmissible, regardless of my respect for its proponent.

By distorting the concept of Nature and conflating the physical natural order with the ethical natural order, Evola also overlooks the existence of the three types of understandings of natural law, which are:

Anthropological optimism, which takes man as the measure of the universe, deems good whatever aligns with his inherently good nature and bad whatever contradicts this inherently perfect nature.

Anthropological pessimism, which takes man as the negative measure of the universe, deeming good whatever is contrary to his inherently bad nature.

The Christian concept of man, according to which he is measured and not the measure, holds that the criterion for discerning what is good and what is bad is determined by God's commandments, the legislator of the universe.

The first understanding is Protestant iusnaturalism, ranging from Grotius to Rousseau and extending into Kant, representing the secularization of Thomistic intellectualism. The second is Hobbes’s anthropological pessimism, which secularizes Scotist voluntarism. The third is the natural law of St. Thomas Aquinas, the Council of Trent, and the Catholic Counter-Reformation.

Evola, however, confines Natural Law to the first of these—Rousseau’s anthropocentrism and anthropological optimism:

"Here we will focus on a particular point: what has been called 'natural law,' a concept that has played a significant role in modern subversive ideologies. The ultimate foundation of this idea is a utopian and optimistic conception of human nature. According to the doctrine of natural law, or iusnaturalism, regarding what is just and unjust, lawful and unlawful, there exist certain immutable principles inherent in universal human nature. This is what has been referred to as 'right reason,' which can always be directly recognized. The set of these principles defines natural law."

Since Vatican II, natural law is no longer that of Saint Thomas Aquinas or the classic scholars of the Spains. Instead, it reflects Rousseau's anthropological optimism. However, Evola has no basis for conflating such disparate types of natural law.

If the Catholic Church today stands as the foremost among Protestant sects, it remains the Catholicism that is not confined to the Vatican apparatus, an unshakable value for Hispanic traditionalists. Against the Vatican, if necessary; more Catholic than the Vatican, if necessary. In fidelity to the dead whose legacy we perpetuate.

We Hispanic traditionalists oppose the abstract man of the revolution, a mere democratic statistic, a plain 'homo economicus.' Instead, we champion the concrete man of Tradition. Born as an hidalgo, a 'son of something': they are members of a family, of a fatherland, hierarchized from birth, and from birth firmly rooted in a concrete sphere of existence.

I am certain that if Julius Evola had reconsidered the exclusivism with which he identified Natural Law with the natural law of the Revolutionary man, and if he had reflected on Natural Law in its true Catholic significance, he would have embraced it as it truly stands: the singular support for Tradition and the ultimate bulwark against the dissolution of the Catholic Church and the political societies of the West, a sobering reality witnessed daily in the latter half of the 20th century.

The hierarchy that the modern world needs to save itself can only be established by upholding the validity of authentic Natural Law—not by dismissing it or confusing it with its Protestant, Rousseauian, and revolutionary degenerations. A strong testament to this is how positivism and Marxism staunchly oppose Christian Natural Law.

Evola's ignorance of the Hispanic nobility of Spirit.

Our reservations about Julius Evola stem from his selective identification of certain historical moments as traditional, notably excluding the Spains of the 16th and 17th centuries—periods that were the true heirs to the Counter-Reformation and the upholders of medieval Christendom's values. For Evola, the Ghibelline Empire represents the final possible embodiment of Tradition. Beyond it, he perceives only emptiness, darkness, and crisis.

An excessively long discussion would be required to fully elucidate the significance of the Ghibelline Empire. For the purposes of this study, we shall accept its validity, with the understanding that any necessary reservations will be addressed elsewhere. For now, let's recognize the considerable value "of that grand Roman-Germanic civilization, articulated and imbued with a metaphysical tension characteristic of the Ghibelline Middle Ages."

What we cannot concede is the notion that with the fall of the Hohenstaufens, all possibility of a restraining action against the excesses of the Church ends, or that true hierarchy, which values each man's respective qualities, vanishes entirely. This is precisely what Evola asserts when he writes that...

"With the Hohenstaufens, tradition has its last luminous flash. Afterwards, Empires will be supplanted by 'imperialisms' and nothing more will be known of the State except as a particular, national and therefore social and plebeian temporal organization."

Setting aside the error of conflating the Empire with a 'Stato,' a misconception since 'Stati' emerged in opposition to imperial authority from the 13th century onward, it is perplexing that Evola failed to recognize that the royal house of Aragon inherited the Ghibelline legacy. This oversight diminishes his understanding of how Tradition persisted and evolved beyond the collapse of the Hohenstaufens, particularly through the Aragonese monarchy's role in maintaining and transmitting the Ghibelline spirit within the broader context of Hispanic Christendom.

The gauntlet thrown by Conradin from the gallows in Naples’ Mercato square was taken up by King Peter III of Aragon, who continued to uphold the Ghibelline banner in Sicily, provoking the wrath of the pro-French Pope Martin IV. This pope went so far as to excommunicate him, following the tradition of his predecessors who excommunicated emperors whose cause Peter III inherited—an excommunication that proved both futile and absurd, as demonstrated by the victory of the Almogavar troops at the Battle of the Col de Panissars. Strangely, Evola makes no mention of this crucial fact in the Rivolta when discussing the Kings of Aragon.

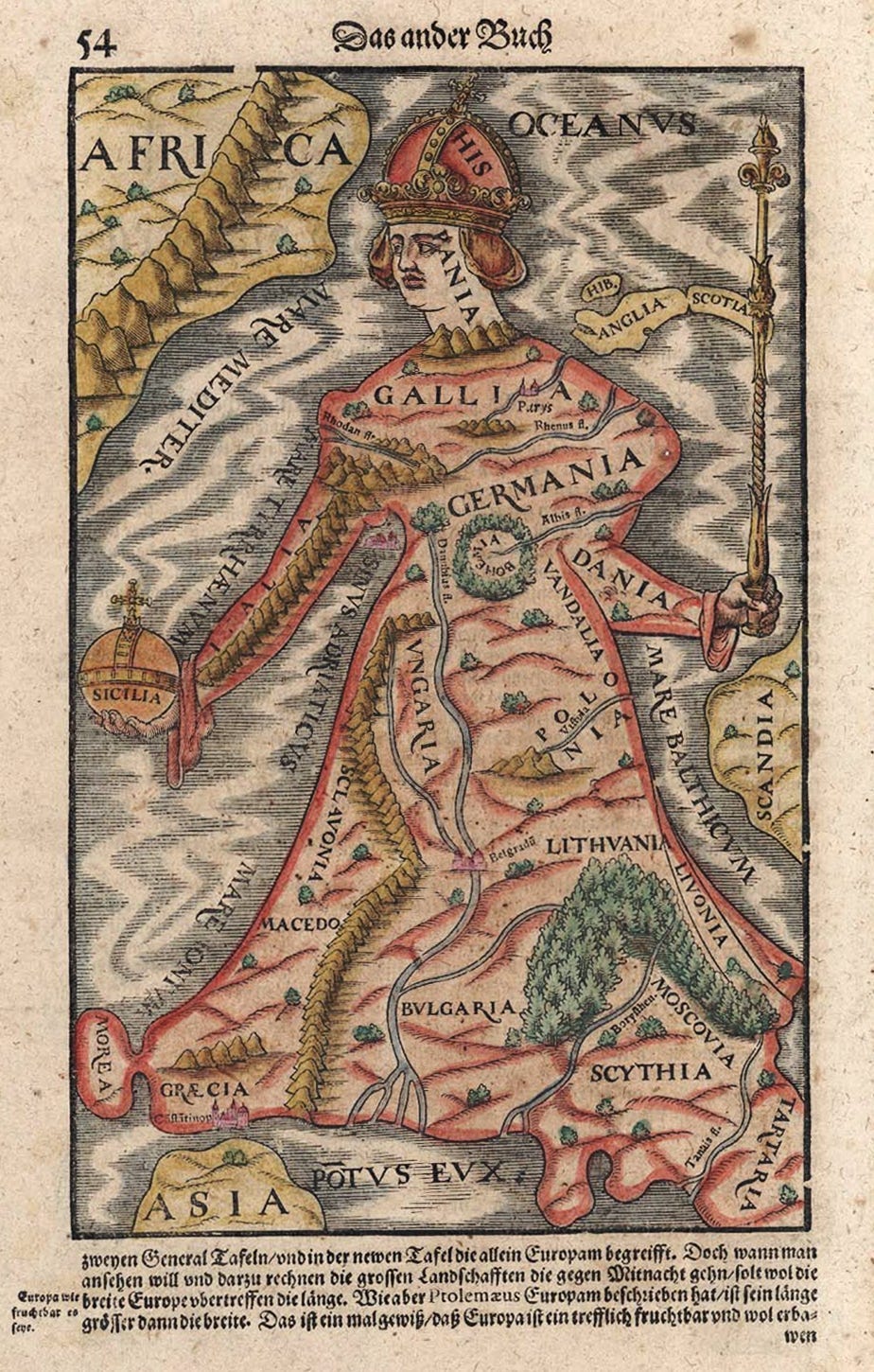

Due to his ignorance—whether deliberate or not—of Spanish history, Evola fails to recognize that during the 16th and 17th centuries, Spain inherited the mantle of the Empire, albeit without the imperial title. Spain became a collection of peoples unified under a single authority, embodying the universalism that was once the hallmark of the Empire.

No one knew how to curb the excesses of what Evola would call the 'priestly caste' as effectively as Charles V and Philip II. The chronicles of the Kingdom of Naples document the abuses committed by Urban VIII and other pontiffs of his ilk. The phrases Evola uses to portray the meaning of the Empire, according to 'the royal idea,' apply more fittingly to them than to the Hohenstaufens or the Swabians. As Evola states…

"According to this idea, the emperor is indeed the caput ecclesiae, not in the sense that the emperor replaces the head of the priestly hierarchy (the pope), but only in the sense that the imperial function can effectively encompass the very force carried by the Church and animating Christendom"

Continuing the portrait of Charles V or Philip II when he adds:

"The emperor... claimed to have directly from God his right and power, acknowledging only God above him: thus the head of the priestly hierarchy, who had consecrated him, logically could only be a mere mediator, incapable—according to the Ghibelline idea—of revoking his supernatural power already assumed through excommunication"

Based on that Ghibelline idea, Peter III of Aragon rejected the excommunication through which Pope Martin IV sought to deprive him of his kingdom. In defense of Christendom against the ambitious whims of popes, Charles V imprisoned one in the Castle of Sant'Angelo, and Philip II detained rebellious bishops in Naples. It is perplexing how Julius Evola could have overlooked such decisive events.

If the Empire collapses, its final champion was Charles V. The collapse of the Empire can be attributed to the Lutheran Reformation, which religiously divided it, and to the failure of the emperors of the 14th and 15th centuries to assume effective powers of command. These powers gradually passed into the hands of petty kings and German lords. This decline was foreseen by the brilliant Raymond Lull in the early 14th century, and his theses were later collected and copied by Nicholas of Cusa in the mid-15th century.

With the collapse of the Empire, which by the mid-16th century had dwindled to a mere title devoid of effective command, Charles V transferred the universal enterprise of the Empire to his son, Philip II, while he left the imperial title to his brother Ferdinand. From 1556 onward, the mission and imperial idea resided in Spain, even as the hollow imperial title continued in Germany. Thus, Christendom was transformed into the universal Monarchy of the Spains, where the universality once embodied by the Empire was found. In the latter half of the 16th century, the Empire remained a fragment of the West, while in the universal domains of the Hispanic world, the sun never set.

All that Julius Evola writes about the decline of the imperial idea in Rivolta is mistaken in overlooking that the imperial function, albeit without the title, was embodied by the universal Monarchy of the Spains. This was a collection of monarchies united under the same king.

These were not absolutist monarchies, as the concrete medieval liberties remained alive within them. Nor were they Guelph monarchies, as they kept unruly popes in check. They were not democratic monarchies, as power was derived from God. Nor were they monarchies of the so-called popular type, as their universal reach encompassed diverse peoples, including Franche-Comté and the Philippines, Naples and Chile, Catalonia and Portugal, Castile and Sardinia, Galicia and Sicily.

Countless citations converge at the tip of the pen, from Luigi Tansillo to Gerónimo Osorio, from Ramón de Muntaner to Hernando de Acuña, from Giambattista Marini to Lope de Vega, from Jean Boivyn to Tommaso Campanella, and from the chronicles of the conquerors to diplomatic documents. All of these confirm the unparalleled imperial sense of an effective universal Empire embodied by the Spains. Evola’s blindness to these values, both factual and ideological, was the greatest obstacle to mutual understanding between him and Spanish traditionalists. He failed to recognize that the last true incarnation of the Empire was not the Ghibellines, but the Catholic monarchy of our Lord King Philip II.

Julius Evola: Assessment from a Catholic Traditionalist Perspective

The extensive intellectual work of Julius Evola has illuminated the importance of the concept of Tradition and the unique value of the concrete traditional man in Italy. From the warlike camps of today’s Hispanic Traditionalism—namely Carlism—we must acknowledge and express our gratitude for his contributions. However, his starting point, ahistorical concept of Tradition, misapprehension of the true concept of Natural Law, and his conclusion of the Empire in Ghibelline times are not acceptable to us.

These divergences are highlighted with the aim of clarification, hoping that his disciples might reconsider such misconceptions of the master. This way, we may reach agreement on ideological foundations in the future, just as we already concur in rejecting the modern world, which is dissolved in its cardinal essences. Especially since the Second Vatican Council betrayed the cause of Christ—the champion of truth’s battles—to fall into the folly of ecumenism as surrender and dialogue as a pact with lies.

Evola's formidable critical apparatus against the factors of decay in the West—dissolving in the anarchic madness of democracies, the hollow skepticism of liberalisms, the egalitarian religion of Marxism, and the infidelity of the Catholic Church to the militant and missionary stance of Christianity—is perhaps the best monument of resistance against so much heresy, barbarism, and destructive folly.

It's a pity that he became a kshatriya, remote and inaccessible from our human surroundings, neither wanting nor knowing how to embody the hidalgo, the supreme exemplar of Tradition as we understand it. I am certain that if Evola had explored the intimate reasons behind his powerful personality, he might have discovered in hidalguía the secret drive that propelled him throughout his entire existence. I hope this for him and his disciples, that he may not remain a mysterious prophet buried in his secrets, but rather become one of the great captains that we traditionalists can follow in this life-and-death struggle against the modern world to which, by sad fate, we have been condemned to live.

The salvation of this world will not be achieved by forging men who serve as a bridge from the present historical cycle to the one that is to follow, as Evola believes when he postulates that in this "Kali-Yuga," the dark age "of terrible destructions, those who unite there and stand firm above all can achieve fruits not easily accessible to men of other ages." This perspective aligns with his view of men as isolated, engaged in a selfish tantrism suited for solitary enterprises.

But rather through the feat of battle-hardened hosts who know how to heed the words of Christ, the one true God for Spanish traditionalists: “But the one who stands firm to the end will be saved” (Matthew 24:13). “But the one who perseveres to the end will be saved” (Mark 13:13). For Christ is the only one who commands with authority, as even the Pharisees acknowledged in the Gospel according to Luke 4:36. In this hour of the abomination of desolation foretold by Christ (Matthew 24:15; Mark 13:14), many will come using His name to deceive us (Matthew 24:4-6; Mark 13:6), and we will be hated for our fidelity to His name (Matthew 10:22). Yet, we will not be deceived because the tree is known by its fruits, just as false prophets are (Matthew 7:15-20). Even if they present themselves as His vicars, we remember that “a disciple is not above his teacher, nor a servant above his master” (Matthew 10:24).

This is, for Hispanic traditionalists, the language of God, without having to resort to the Sanskrit texts of the "Devanagari." This is how we wish to be. To express it in Sanskrit: rayáskamo viçvapsnyasya, longing for eternal wealth. Just like our noble ancestors, we Spanish traditionalists possess the will to fight the sacred battles of the Lord against this secularized world.

In these battles, Julius Evola can and should be one of the most distinguished champions.

Traditionalist Neapolitan thinker who wrote against the Risorgimento.

A list comprising Carlist intellectuals.

Jaime Balmes was a Catalan theologian who advocated for the modernization of Thomism. Simultaneously, he adopted a somewhat liberal-conservative stance on the dynastic question, envisioning unity between the Carlist and Liberal branches of the Bourbons in Spain.

Donoso Cortes never advocated for the Carlist branch of the Bourbon dynasty during the Carlist War in Spain. Instead, Donoso defended what Schmitt called "commissarial dictatorship," which Donoso interpreted as a means to halt the upheaval caused by Leftism and to return to a more traditional state of affairs. This program of "returning" was not present in Schmitt’s concept of dictatorship nor in his idea of restoring the Ius Publicum Europaeum.

Marcelino Menéndez y Pelayo was primarily a literary critic. His political leanings aligned more closely with the conservative-liberal party of the Unión Católica, i.e., not a Carlist.

Ramiro de Maeztu was initially inspired by positivist and socialist ideas until he converted to Catholicism and became a conservative. He did not support the Carlists.

Vicente Marrero, although a Carlist, held in high regard the aforementioned conservative-liberal figures like Balmes and Donoso in his book titled "El poder entrañable" (1952).

See note 5. Alejandro Pidal was the head of Unión Católica.