The Bourgeois Thought Form and the Political Nation

ON REVOLUTIONARY TOTALIZATION: THE LOGICAL DETERMINATIONS OF THE POLITICAL NATION

Note (Captatio Benevolentiae)

This essay was written for my undergraduate course on Hegel. Its style may come across as somewhat clunky, repetitive, and pedagogical to the extent of exhaustion, a consequence of being crafted specifically for a college-level class rather than with publication in mind. Additionally, I heavily procrastinated, which led to a rushed completion—particularly evident in the final sections of the essay. I ask for your understanding regarding the stylistic choices—such as constant citations and proofs of a student’s textual comprehension—made under these circumstances.

The primary purpose behind the publication of this essay is to provide a concrete example of what Panagiotis Kondylis refers to as the “bourgeois thought form” in his book The Decline of the Bourgeois Thought Form and Life Form, a work rather infamous in our circles for its lack of illustrative examples. Simultaneously, it is not uncommon to encounter, in our small group chat, recurring questions about the precise reality to which Kondylis refers. This work is primarily intended for them.

Consequently and in my view, this work captures the essence of the bourgeois thought form by employing Hegel’s Science of Logic as the central interpretative tool for understanding the nature of the political nation—that is, the political structure that emerged in the wake of the French Revolution.

On the other hand, asserting this might seem almost trivial, given that Hegel is, without question, the quintessential culmination of “bourgeois thought.” His system represents, at its core, a philosophical journey toward the reconciliation of self and world—a journey that is far from straightforward, marked instead by dramatic returns, shifts, and contradictions, or what Hegel terms negativity. Hegel’s greatness lies precisely in this: the collapse of exteriority and its subsequent integration within the self. Whether we accept this as truth or regard it as a joke, as Kierkegaard might have, is a question for another time.

Because of this, Kondylis undoubtedly had Hegel’s speculative philosophy in mind while writing his book. The Greek’s description of the bourgeois thought form as “synthetic-harmonizing” precisely refers—without explicitly mentioning him—to the journey outlined by Hegel in his Logic:

The part exists inside of the whole, and it finds its determination by contributing to the harmonic completeness and perfectness of the whole, but not by denial of, but by the development and unfolding of its own individuality.

There are a few key points to emphasize here. First, the individual parts—though they may exist in a state of difference, or more precisely, discontinuity (and perhaps even contradiction)—must be harmonized into a whole. In Hegelian terms, this harmonization could be described as a speculative moment. Secondly, the parts are perceived in their individuality, which brings us to the question of voluntarism: individuals will overcome the constraints of tradition. This view stands in stark contrast to how parts were conceived under the ancien régime, where they were not “atomistic” but “anatomical”—guilds, nobles, peasants, etc. For a more thorough explanation, you can just read Kondylis yourself. ;)

It is important to state, however, that I only mention Kondylis’ work once in this essay, and only to highlight a minor point regarding the continuity between absolutism and revolution. Rather, I primarily rely on Gustavo Bueno and Hegel to elucidate the determinations of the political nation. That said, I must emphasize that all three authors are referring to the same reality—namely, that of the bourgeois thought form.

ON REVOLUTIONARY TOTALIZATION: THE LOGICAL DETERMINATIONS OF THE POLITICAL NATION

Introduction

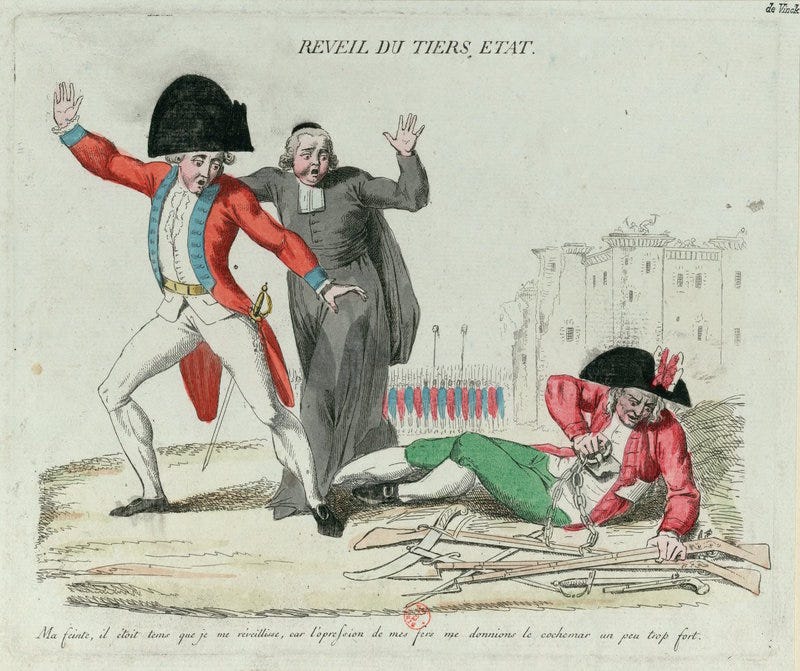

In “Work and Revolution in France” (1980), William H. Sewell declared that the French Revolution was a “radical transformation of the entire social order” (62). Sewell further observes that, in the eyes of its makers, the Revolution sought to “dismantle the hierarchical social framework of the old regime” (ibid.), a process that necessarily involved a direct assault on the metaphysical presuppositions (or ideology) that both legitimized and (in)formed the corporate social formation of the ancien régime.

Among these shifts, one holds essential importance for this investigation. It lies at the intersection of the sphere of subjective representations and the plane of subjective realities—namely, the totalization of society. By totalization, we refer to the way in which the parts of a political society are reorganized into a whole: how the corporate totality of the old regime was transformed into the revolutionary political nation. The elucidation of the mechanisms underlying this shift constitutes the principal programmatic orientation of this work.

These mechanisms inexorably follow a dialectical logic, primarily because the object of our analysis—namely, the shift between two ways of totalizing society—ineluctably refers to notions that are canonically tied to the idea of dialectics. The word shift evokes movement, a philosophical principle that dialectical materialists such as M.A. Dynnik, in his History of Philosophy (1968), elevated against the “undialectical” (79) eleatic school, which denied the possibility of movement altogether1.

On the other hand, the subordination of dialectics to totality (and thus totalization)—understood in monist terms as the assertion that “everything is interconnected, and there is a continuous process of change within this interrelation” (Sierra, 88)—is evident in the works of renowned dialecticians such as G. Lukács, who writes that:

“The true, materialist-dialectical totality, in contrast, is the concrete unity of struggling contradiction. This means: first, that without causality, there is no living totality. Second, that every totality is relative in both directions, that is, constituted out of subordinated totalities and entering as an element of a subordinating totality.” (Lukács, 190; emphasis added)

In this paragraph, totality is linked to dialectics through contradiction, which, according to the philosophical tradition, serves as the leitmotif of dialectics. This is the common thread uniting Aristotle and Kant with Plato and Hegel: the association between dialectics and contradiction. However, this investigation aligns more closely with the approach of the latter than with that of the former—contradiction is not confined to the sphere of method, syllogisms, or thought but extends into the realm of being. It is crucial to note, however, that this perspective only holds if we assume the dichotomy between being and thought, a distinction that is pre-Hegelian in nature.

That said, the mechanisms or logic underlying the transition from a corporate-based totality to a political nation adhere, therefore, to the triadic schema of dialectical movements described by Hegel in the Encyclopedia (1975):

A moment of Understanding, which “sticks to fixity of characters and their distinctness from one another” (§80). Politically, this corresponds to the primordial totality of the corporate state, i.e., the kingdom of quality, characterized by clearly delimited parts arranged vertically within a hierarchy.

The proper dialectical moment of negative reason, which identifies the limits and contradictions within Understanding in its fixity. This is the stage of contradiction, division, and opposition, marked by the “we admit one, but we also admit the other also” (§81). Politically, it corresponds to the quantitative decomposition of the corporate whole into equal, atomic parts.

The final stage is that of speculative or positive reason, which “apprehends the unity of terms in their opposition” (§82). This stage entails the re-totalization and return to the now-mediated whole, forming a new totality, i.e., the political nation where its members participate as equals under the law.

It is nonetheless important to keep in mind that within these triadic stages multiple movements are occurring. The common interpretation of dialectics as thesis/antithesis/synthesis—primarily Fichtean (The Science of Knowledge, §3)—does not precisely correspond to the transition we are describing. Dialectical notions, consistently present in Hegel’s analysis, such as the immediate and the mediated, or the interplay between the forces of negativity and reflexivity, also operate within the logic of these stages. However, the main Hegelian categories used to elucidate this transition from one totality to another are those found in the Science of Logic (2010)—namely, the quality-quantity pair and the finitude-infinitude relation—as they are most capable of directly addressing this shift, even though it is certainly possible to capture this transition using different categories.

The First Determination of the Political Nation: The Corporate State

The Corporate State as the Dialectical Diallēlos

Before engaging with the corporate state as the moment of Understanding within the determinations surrounding the political nation, it is first necessary to clarify the position that this social whole or formation holds in the constitution of the political nation. Our narrative, here, is proleptic, as we assume the existence of an established political nation and, in the manner of a regresus, trace back to its initial determination; the corporate state. Without this prior apprehension of the nature of the corporate state, and thus of the dialectical logic underlying the constitution of the revolutionary totality—the political nation—our understanding will remain incomplete and obscure.

Here, the corporate state represents the totality that, due to its historical proximity, initiates the determinations of the political nation. In this aspect, the social formation of the ancien régime serves as the immediate whole. Which, in the speculative stage, is transformed into a new totality while retaining, in a certain sense, its identity.

The corporate state is, therefore, a diallēlos for the political nation. Diallēlos refers to a “circle that occurs in an argument or discourse, wherein one begins by admitting what is to be demonstrated” (Bueno, 303). To the ancient Greeks, particularly those associated with Pyrrhonism, the diallēlos was interpreted as a vicious circle. And thus a mode or trope used to justify the suspension of judgment (epoche), i.e., skepticism. In fact, it was Diogenes Laertius who claimed that the skeptic Agrippa described the diallēlos as the ho diallelos tropos (the mode of reciprocity), which the doxographer outlines in the following terms:

The mode arising from reciprocal inference is found whenever that which should be confirmatory of the thing requiring to be proved itself has to borrow credit from the latter, as, for example, if any one seeking to establish the existence of pores on the ground that emanations take place should take this (the existence of pores) as proof that there are emanations. (Laertius, §89)

But not everyone identifies the diallēlos as a vicious circle that leads to skepticism. For the Spanish philosopher Gustavo Bueno, the diallēlos is “indispensable for scientific construction,” and he offers the example of anthropology, which presupposes the existence of humans, since, as the author states, “it would be absurd to construct the figure of the historical man directly from primates” (Bueno, 303). In anthropology, then, the human appears as a given, even when one seeks to explain its genesis. Mutatis mutandis, the political nation entails the prior existence of the corporate state.

This phenomenon might seem trivial, as in history, nothing arises from nothing (although, as we know from the logic of being, nothingness and being are indistinguishable). Due to a mere question of historical proximity, the assertion that post-revolutionary society emerged from the structures of the old regime simply constitutes a truism. Nor is this an original thesis: affirming the continuity between absolutism and revolution was a conservative commonplace long before Tocqueville wrote The Old Regime and the Revolution (1856). Panagiotis Kondylis, in Konservatismus (1986), succinctly explains the continuity between the centralism of absolutism and the new revolutionary totality in the following terms:

Centralization is the direct expression of modern sovereign statehood, because it brings about the state independence of all individuals, which is possible only because the rule of the oikos leaders over their own 'people' is eliminated; But if it is eliminated, then no distinctions of status and no statuses remain, man appears as an autonomous individual and no longer as a member of an oikos… (Kondylis, 215)

Yet, the identification of the corporate state as a diallēlos extends beyond (while still encompassing) this “Tocquevillian continuity” between the old and new regimes. This is primarily because the latter merely underscores what these social wholes shared in common, without engaging with the determinations involved. What is missing from this picture is, precisely, Hegel, as the diallēlos is, by its very nature, dialectical.

In this sense, the corporate state is what becomes sublated. Sublation (aufheben) entails both preservation and cessation; it is, therefore, not merely continuous but, if you will, a continuous discontinuity or a negative continuity. Regarding aufheben, Hegel asserts that “what is sublated is thus something at the same time preserved, something that has lost its immediacy, but has not, for that, become nothing” (Hegel, 82). This political diallēlos is, as previously stated, the primal totality that becomes mediated and transforms itself into a new whole while preserving its identity: the process of sublation here entails a return, now filtered through the effects of negativity on that initial totality.

Moreover, that the socio-political morphology of the ancien régime serves as the diallēlos of the political nation signifies, in terms of immanence, that it constitutes the sphere upon which subsequent dialectical operations of determination are applied. It is the social whole of the corporate state that becomes divided into atomic parts during the moment of negative reason. Those same parts are then speculatively re-formulated into the political nation, a totality of citizens equal under the law.

At last, before going further, it is crucial to emphasize that the corporate state, as a diallēlos for the political nation—ultimately signifying the transformation of one identity into the same but now mediated identity—is historically circumscribed to a select group of Western European political societies, such as France, Spain, Germany, Italy, etc. Bueno, in “El mito de la cultura” (2004), refers chauvinistically to these nations as “canonical,” meaning that they emerged directly from the political morphologies of the ancien régime, as opposed to continental nations like Russia or the United States, or merely regional nations, which for Bueno are, echoing Engels's idea of Völkerabfälle (1849), mere ideational constructs (e.g., Basques, Catalans, Welsh, or Bretons).

The Corporate State as the Kingdom of Quality

The moment of Understanding within the logic of the political nation is the corporate state. By corporate state, we refer to the social formation institutionally organized through morphological parts strictly differentiated by legal, political, and social means, such as the Throne and the Altar; estates (nobility, clergy, people); professions (medics, lawyers, teachers, soldiers, peasants); the various orders within the clergy; etc. Its intellectual reflection is embodied through the medieval doctrine of the scala naturae: a well-ordered vision of Nature, hierarchically structured by God. St. Augustine beautifully elucidates this concept in the Enarrationes:

a terra usque ad coelum, a visilibus ad invisibilia, a mortalibus ad inmortalia. Ista contextio creaturae ista ordinatissima pulchritudo, ab imis ad summa concedens, a summis ad ima descendens, nusqueam interrupta, sed dissimilibus temperata, tota laudat Deum. (Enarrationes in Psalmos, Psalm 144, Section 13)

Its social expression took the form of a vertically organized system: a “pyramidal shape long associated with divinity and which expresses unitary power, hierarchy, and stability” (Maza, 15). Moreover, it is essential to emphasize that this image of the world, when translated into the social sphere, had a predominantly qualitative orientation. It conceived the components of the socio-political body not as individualized units but as naturally formed layers of differentiated groups.

The morphological parts of the corporate state were understood in qualitative terms, which underpins the estate as the organizing principle of its social structure. In this “city of God,” society was vertically organized into three distinct groups, each following its own code (rights and obligations): oratores (those who pray, i.e., the clergy), bellatores (those who fight, i.e., the nobles), and laboratores (those who work, i.e., the serfs). These estates, in the qualitative observations of Charles Loyseau, represented the “dignity and quality” that were “the most stable and the most inseparable from a man” (Loyseau, 3). The social importance of these parts was, therefore, functional rather than numerical: a body has a heart, liver, brain, and lungs, not a ratio.

In this case, a strong orientation towards social fixity—meaning a lack of mediation—prevails, which, as could not be otherwise, is inherent to the qualitative logic underlying the organization and social totalization of the corporate state. Bueno, in Algunas precisiones sobre la idea de holización (2010), described this mode of totalization as “anatomical,” due to its resemblance to the medical sciences of antiquity and medieval times, which he defines in the following terms:

These involve partitions (or groupings) of totalities 𝑇 into strata or heterological layers, assembled within the whole but without direct consideration of their isological elements. Anatomical rationalization proceeds by decomposing the whole into heterological parts (without prejudice to enantiomorphic symmetries, similarities, or proportions between them), even irregular ones (such as fractals), which are pre-established through practice. (Bueno, 29)

This description of the corporate state’s mode of totalization is overtly scholastic to the point of obscurity. However, from a single sentence—“without direct consideration of their isological elements”—it becomes possible to offer a dialectical picture of this entire process. By isological, Bueno refers to the relations between parts that share the same structure. For example, a group of coins shares an isological relation with one another inasmuch as they are all coins. Heterological relations, in contrast, refer to relations between parts that differ in structure: a group of coins from different countries with different designs has a heterological relation among its members.

The corporate state ignores the potential homogeneity among its parts, favoring instead a qualitatively differentiated conception of the social whole. This emphasis underpins the fixity of the first determination of the political nation; it dismisses the equality of its parts, sustaining itself in a reified state of being—an immediate social order. Such an outcome arises because the corporate state remains confined within a qualitative framework for understanding the social world. To understand this moment of fixity framed as the prevalence of quality over quantity it is of great value to cite Hegel´s distinction of these categories:

Quality is the first, immediate determinateness. Quantity is the determinateness that has become indifferent to being; a limit which is just as much no limit; being-for-itself which is absolutely identical with being-for-another: the repulsion of the many ones which is immediate non-repulsion, their continuity. (Hegel, 152)

Quality represents an internal determination of being; it is what an object intrinsically is, defined and mediated by a qualitative limit—that is, by the other, or what it is not. For instance, to be a noble entails not being a priest or a member of the third estate, and vice versa. The parts of the corporate state operate within this circuit of quality, participating in the whole as qualitatively distinct groups. In contrast, quantity is an external determination of being, indifferent to change: 500 nobles remain nobles even if 500 more are added. This indifference to change embodies the principle of equality essential for the development of the political nation.

Being bound by the logic of quality implies that the corporate state has not yet reached its quantitative determination: the political participation of each estate is qualitative, not dependent on the number of its members. For such a development to occur, it is necessary first to interpret the parts of the body politic in terms of the external determinations of being, rather than their internal, qualitative characteristics. The interpretation of isological-homogeneous relations as quantitative is a development we will explore in the next section.

The Moment of Negative Reason: The Emergence of the Quantity

As stated previously, the totalization of the corporate state sustains itself in qualitative terms: the parts of the ancien régime participate in the whole as qualitatively distinct groups, independent of their numbers. This corresponds to a sense—characteristic of the moment of Understanding—of fixity framed in qualitative terms, as it is incapable of analyzing the homogeneous components that exist within those parts. The recognition of these homogeneous components marks, within the logical determination of the political nation, the moment of negative reason, where the conceptual fissures of Understanding ultimately implode under the force exerted upon them by negativity.

Using the terminology from the doctrine of being, being-for-itself represents the culmination of quality, arising from the synthesis of its two moments: immediacy—positivity or something, and its negative limit, the other. Being-for-itself is thus a relation with itself, mediated by an other: an identification achieved through negation. From this stage, the one (atom) emerges as an identity (unity) that excludes the many (multiplicity)—that is, the other ones. At this juncture, quality stands at the threshold of quantity. The atom excludes all externalities to such an extent that quantity emerges precisely as that which is not quality, that is, as “sublated being-for-itself” (Hegel, 154). As D. Carlson argues, “quantity is quality as pure relation, divorced and separate from the parts which it relates” (Carlson, 2031).

The main point to underscore is that quantity, unlike quality, represents an external determination of being. It is indifferent to both content and change: two kilograms of water remain water, even if an additional kilogram is added. The atom—or the individual, as Boethius translated the term into Latin—is indifferent to its internal determinations. In this sense, it emerges as a blank slate, an undifferentiated unit devoid of qualities, of content, which is what Hegel refers to as pure quantity.

This transition from quality to quantity underpins the positing of the abstract human the central part of the social whole in the first article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man (1789): “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights,” in stark contrast to the qualitatively determined subject of the corporate state. What commonality exists between a noble, a priest, a peasant, and a bourgeois? Their bare humanity. From this operation emerges a pure human—stripped of traditional qualitative determinations such as race, profession, or class—conceivable only within the logic of quantity, which is fundamentally indifferent to any qualitatively informed content.

Revolutionary reason fragmented (diaresis) the qualitative parts of the ancien régime, an analytical process culminating in the figure of man qua man—the pure human devoid of any qualitative determination, the human-as-an-atom. From this revolutionary transition of quality into quantity emerges the figure of the abstract man: human as a quantitative unit. The naked man thus becomes the new constituent part of a not-yet-fully-formed social whole, liberated from the material determinations of history. This dynamic underpins Liberté as revolutionary freedom—a freedom from the deep chains of inherited tradition.

Simultaneously, the equality (Égalité) of these parts emerges precisely from the analytical dissolution of the qualitative distinctions of the corporate state. This naked man, stripped of all content, becomes equal to other naked men, similarly devoid of any attributes that would render them distinct. Returning to the language of the pure determinations of thought, Hegel ascertains the equality of these parts in his discussion of continuity and discreteness: magnitude—general quantity in its non-concrete form—contains two mutually entailing moments: continuity and discontinuity. Continuity implies the divisibility of the continuous whole into atomic parts, while discontinuity is continuous because all these atoms, as simple units without content, are equal to one another:

In continuity, therefore, magnitude immediately possesses the moment of discreteness – repulsion as now a moment in quantity. – Steady continuity is self-equality, but of many that do not become exclusive; it is repulsion that first expands self-equality to continuity. Hence discreteness is, for its part, a discreteness of confluents – of ones that do not have the void to connect them, not the negative, but their own steady advance and, in the many, do not interrupt this self-equality. (Hegel, 154)

Ernest Renan, one of the leading theoreticians of the French nation, showed this quantitative abstraction when he asserts: L'oubli, et je dirai même l'erreur historique, sont un facteur essentiel de la création d'une nation (Renan, 37). The French were required to forget their qualitatively informed origins—Franks, Gauls, and Normans—to reemerge as a clearly delineated nation of citizens equal under the law. Mutatis mutandis, for the French to become a political nation, they also had to erase their distinctions as nobles, bourgeois, peasants, lawyers, and so on.

It is the logic of quantity that serves as the foundation for both equality and liberty; the abstraction of quantity from all content-related determinations allows the conception of men as equals and free with one another to emerge. Simultaneously, it is this same logic of quantity that underpins revolutionary political participation, as the parts of the social whole are no longer understood through their qualitative functions but through their numerical value. This shift enabled abbé Sieyès to draw the following comparison—one that would have been inconceivable under the totalization of the corporate state:

Therefore, in total, there are less than 200,000 privileged individuals of the first two orders. Compare their number with the 25 or 26 million inhabitants, and draw your own conclusions. (Sieyès, 7)

Nonetheless, reducing the dialectic of the political nation to a mere transition from quality to quantity remains insufficient, as the circle is not yet closed. A speculative step becomes necessary because bare humanity alone cannot sustain a political body, not only due to practical limitations but also because it is logically inconclusive. The number, as a unit (an atom), when expressing a determinate magnitude (such as seven or eight), “become” a quantum. It is at this point that quantity reaches its false or incomplete infinitude. In an infinite progression, a number is surpassed not by infinity itself but merely by another number—an operation that similarly applies in reverse, with negative numbers. It is a “perpetual generation of the infinite, without the progress of ever getting beyond the quantum itself, and without the infinite ever becoming something which is positively present” (Hegel, 191). For any given number, there is always one that is larger and another that is smaller.

The challenge now is that if we remain at this negative state of quantitative dissolution—where the corporate state’s political morphologies are reduced to atomic parts—the reconstruction of those parts into a sublated new political reality becomes chimeric. This is because such atomic units exist in a state of vagueness and dispersion, diluted into an anthropological abstraction of humanity.

These were precisely the criticisms leveled by an opponent of the French Revolution like Edmund Burke in Reflections (1790): a human stripped of all qualitative determinations (rank, race, nation, etc.) is, in his view, reduced to something closer to an animal. In essence, when applied to the human, quantity evokes animality. To overcome this, it becomes necessary to regroup these atomic parts into a new internal determination—namely, to make the speculative turn of transforming quantity into quality.

The Speculative Moment and the Political Nation as Measure

After the effects of negative reason on the qualitatively informed social morphologies of the corporate state, a speculative step becomes necessary, transitioning from analysis to synthesis. The issue now is that the consequences of negativity have left us with an indeterminate number of atomic parts, existing vaguely within an anthropological notion of humanity. In this sense, a return to quality is required—not merely a restoration or uncritical return to the past, but a sublated return, a new whole that unites both quality and quantity. These multiplicities of atomic parts require a new qualitative consistency, one that halts the infinite regression or progression characteristic of quantity, sets boundaries to this “bad infinity” (Hegel, 192), and forms a renewed totality that encircles all these atomic parts together.

The notion of the corporate state as the diallēlos becomes crucial here, as it establishes the territory—the logical circuit—necessary to prevent the potentiality of political nihilism, that is, the complete dissolution of the atomic parts into some vague notion of Humanity. Logically, the determinations of the political nation are not external, nor do they emerge from nothing; rather, they immanently operate within an already established sphere of quality, that is, the corporate state. Totalization, in this sense, occurs through the absorption of these scattered atomic parts into the new whole of the political nation—an entity that was swiftly attacked by the forces of Reaction. It is not arbitrary that, against the Prussian forces, the French troops commanded by Kellerman at the Battle of Valmy shouted Vive la Nation! rather than the traditional Vive le roi!

France, in this context, was not abolished but rather reconstituted within itself into a new whole. The dialectic of the revolution, the revolutionary method, halted at France (and later, respectively, at Italy, Spain, and Germany) as a qualitatively distinct entity, for its field of operations was circumscribed by the structures (state or canonical nation) that had already existed from the outset. The phrase “for each Nation, a State” should be reformulated, without prejudice of sounding ridiculous, into “for each already historically constituted morphology, a political nation,” since this was the effective logical operation founded by the French Republic in 1792.

France, as a political nation, represented the speculative transition from quantity into quality. In this sense, it contains a multiplicity of atomic parts (now conceived as citizens) that are both equal and free, while also existing as a finite qualitative unity in itself—meaning that France is a not-Germany, not-Italy, or not-Britain. It is here that we posit the idea of Fraternité, which metaphorically relates to the qualitative and private relationships of the familial sphere, now sublated into the unity of all parts within a qualitatively distinct sphere. The political nation is, then, a measure, completing the determination of being and transitioning into the doctrine of essence—a quantitative quality or a qualitative quantity. Allow us to quote Hegel in extenso to clarify the concept of the political nation as a measure:

Measure is the simple self-reference of quantum, its own determinateness in itself; quantum is thus qualitative. At first, as an immediate measure it is an immediate quantum and hence some specific quantum; equally immediate is the quality that belongs to it; it is some specific quality or other. – Thus quantum, as this no longer indifferent limit but as self referring externality, is itself quality and, although distinguished from it it does not extend past it, just as quality does not extend past quantum. Quantum is thus the determinateness that has returned into simple self equality – which is at one with determinate existence just as determinate existence is at one with it. (Hegel, 288)

Quantum is thus quality. It might be useful to explain this passage with two examples: Celsius, as a measure, contains both quality and quantity through temperature: starting from 0°C and 98°C, the quantitative change entails a qualitative change in the states of water (solid, liquid, gas). A minute is also a quantum of time, and time contains an infinitude of units: millisecond, second, minute, etc. Notice that here, temperature and time contains an infinite number of quantities, just as the political nation, in its negative moment, contained a number of indeterminable atomic parts, all diluted in the notion of the naked human.

This transition from quality into quantity, and back again into a sublated quality, is the speculative process that underlines the genesis of the political nation: a revolutionary construction opposed to the static and theocentric hierarchies of the ancien régime. In this way, the revolutionary totalization occurred, synthesizing the atomic parts resulting from the negative destruction of previous qualitative parts into a new social whole. This is the story of the dramatic process of the revolution that shook 19th-century Europe, viewed from the perspective of the pure determinations of thought. In this sense, the drama and epic behind the logic translate—inevitably so, as both are interwoven—into the drama and epic of the social world.

Bibliography

Aragués, Rafael. Introducción a la Lógica de Hegel. Editorial Herder, 2020.

Bueno, Gustavo. Algunas Precisiones Sobre la Idea de «Holización». El Basilisco, no. 42, 2010.

Bueno, Gustavo. El Mito de la Cultura. Editorial Prensa Ibérica, S.A., 1996.

Bueno, Gustavo. El Mito de la Izquierda. Ediciones B Grupo Z, 2004.

Carlson, David G. "Hegel’s Theory of Quantity." Cardozo Law Review, vol. 23, 2002, pp. 2027. Digitalized by Cardozo Law School, https://larc.cardozo.yu.edu/faculty-articles/39.

Diogenes Laertius. Lives of Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 1, Books 1-5, translated by R. D. Hicks, Loeb Classical Library No. 184, Harvard University Press, 1925.

Engels, Friedrich. "The Magyar Struggle." Neue Rheinische Zeitung, Jan. 1849, MECW, vol. 8, p. 227. Digitalized by Marxists.org, https://marxists.architexturez.net/archive/marx/works/1849/01/13.htm.

García Sierra, Pelayo. Diccionario Filosófico de Pelayo García Sierra. 1999. Digitalized by Abertzale Komunista, https://www.abertzalekomunista.net/images/Liburu_PDF/Internacionales/Garcia_Pelayo/Diccionario_filosofico-Manual_de_materialismo_filosofico-K.pdf.

Hegel, G. W. F. Hegel's Logic: Being Part One of the Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences (1830). Translated by John N. Findlay and William Wallace, 1st ed., The Humanities Press, 1975.

Hegel, G. W. F. The Science of Logic. Translated by George di Giovanni, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Kondylis, Panajotis. Conservatism: Historical Content and Downfall. Klett-Cotta, 1986.

Loyseau, Charles. Traité des Ordres et Simples Dignitez. In Les Oeuvres, Paris, 1666.

Lukács, György. The Culture of People's Democracy. Translated by Tyrus Miller, Brill, 2013.

Maza, Sarah. The Myth of the French Bourgeoisie. Harvard University Press, 2003.

Renan, Ernest. Qu’est-ce qu’une nation ? Digitalized by Jean-Marie Tremblay, professor of sociology at Cégep de Chicoutimi. https://upvericsoriano.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/renan_quest_ce_une_nation.pdf.

Sieyès, Emmanuel-Joseph. What is the Third Estate? 1789. Digitalized by the University of Oregon, https://pages.uoregon.edu/dluebke/301ModernEurope/Sieyes3dEstate.pdf.

Sewell, William. Work and Revolution in France. Cambridge University Press, 1980.

Tocqueville, Alexis de. The Old Regime and the Revolution. Translated by John Bonner, Harper & Brothers, 1856.

Trazak, V. Enarrationes in Psalmos CL-CL. Edited by VRNHOLTI, Corpus Christianorum Series Latina, vol. XL, Brepols Typographi Pontificii, 1956.

Dynnick, M. A., M. T. Iovchuk, B. M. Kedrov, M. B. Mitin, and O. V. Trajtenberg. Historia de la Filosofía. Translated by Adolfo Sánchez Vázquez, Editorial Grijalbo S.A., 1968.

Nonetheless, reducing the term dialectics to a mere question of movement is unjustifiable, at least according to the philosophical tradition. Otherwise, Plato would not have identified Zeno—whose paradoxes are explicitly aimed at denying the possibility of movement—as the founder of dialectics.

This guy's good.